Just in case anyone was wondering… TIDE: Trophic Cascades and Interacting Control Possess within a Detritus Based Ecosystem.

Photo credit to Caitlin.

Hello, my name is Nathan Andrews, and I am a TIDE REU (and proud of it!). I am a Marine Biology major at the University of Rhode Island. I am a rising Junior and play rugby for the Rhody Men’s Rugby Club and for the Semiprofessional Rhode Island Rebellion League. I have a very vast interest in the Marine Bio World. My interest range from diatom genetics, to population dynamics of horseshoe crabs, to marine ecology and fish. During the school year, I work in the Rynearson Lab at the URI Graduate School of Oceanography as a lab intern researching diatom genetics and in the past I have worked as a marine educator for Save the Bay, Narragansett Bay, RI. You can only imagine the excitement that fell upon me as I read the job description for this REU position and applied to work as an undergraduate researcher for MBL, and get paid for it! It was a no-brainer.

I intend on using this fellowship to build upon my academic background, as well as gain experience in the Marine Ecology field. I am very interested in Oceanography and intend on going to graduate school to get masters in it. I love science, and my love for science is only matched by my love for the ocean and all of her wondrous functions, niches, and organisms. Science has so much to offer the world and so much ability to heal it, protect it, and renew it. Biology offers me five things: a rewarding career, fieldwork where I get my hands full of science, lab work where I test the truths of nature, and deriving scientific results, which when results are produced it yields new knowledge of the world around us. This excites me!

Life here at Marsh View Farm is awesome. Here, I live with other undergraduate researchers, Marshal, Caitlin, Wesley, and David, and our wonderfully scientifically inclined, helpful and most talented RA, Belle; all of whom are just as excited about marine science as I am! We are lead by Dr. James Nelson (aka Jimmy), who is extremely knowledgeable about everything that is remotely scientific and has been a phenomenal mentor thus far. In this TIDE program, we are more than just members of a scientific community; we are like a family here. We all work together on each other’s projects and we all pitch in when one of us needs help. Being a scientist, under these conditions and within this program is a great lifestyle, and it is something that I would gladly commit my life to.

Here at the marsh, as they say, the “tides wait for no one.” This could not be truer. Our lives are run by the tide. 3 days a week we lug a ton (literally a ton) of fertilizer out to the marsh on the TIDE John Boat, the Apeltes, and do a fill. We all pitch in to help the six projects going on here during the times when we are not catering to the tides to do the fill, once a month we take sediment core samples, once a month we pull about a 48hr shift and do flume nets, and once a month we do a week of sane net collecting 1000 chogs and about 2000 grass shrimp per creek and spend a couple weeks analyzing the collections. Lots and lots of Science!!! And each of these activities and the times that we get up to do them in the morning, afternoon and night, are dictated by the tides.

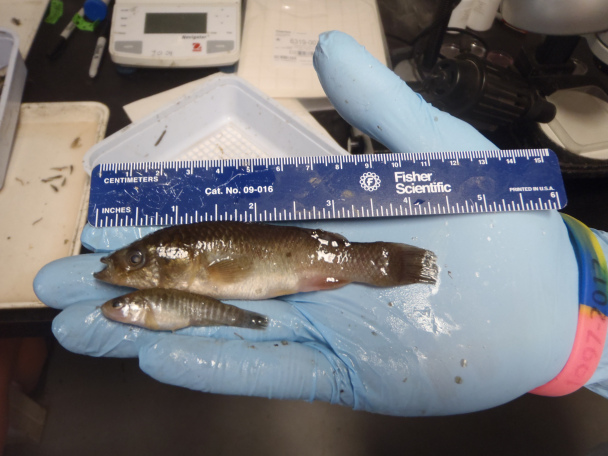

David and I are both being mentored by Jimmy. We are researching nekton of the marsh creeks, looking at mummichogs and striped bass population and energetics. I am particularly looking at growth, diet, and energetics. To determine the growth of the ‘chogs, we do a length frequency analysis. Once a month we do a week of sane net collecting 1000 chogs and about 2000 grass shrimp per creek and spend a couple weeks analyzing the collections. Each fish and shrimp is counted and measured. Chogs and shrimp are major food sources for the striped bass. ‘Chogs hatch on full moons and each month that they are born there is a certain survivorship. This can be determined through their size and number for that particular size range. Fish hatched during the same time are known as cohorts. These cohorts and there alteration in size can be monitored throughout the summer. This data can be used to assemble a graph that plots biomass over time and growth rate over time. The point immediately after the intersection of this two lines gives us a projection of where the max yield and max reproductive potential of the fish can be achieved to form a sustainable fishery. This is important to know because of the extreme interconnectedness of the ocean and her food web, we can monitor changes in other populations due to the change in the ‘chog population. The same analysis can be done for the shrimp.

I have not really gotten into the energetics and diet portions of this project so I will leave that and discussing flume netting for next time! I hope this gives you a good understanding of what is going on here in TIDE. This is an amazing program and a fantastic opportunity for me. I am getting paid to do what I love! I get to go out almost every day and play in the mud and catch fish, every kid’s dream. I get to soak in the sun and enjoy the sites and sounds of the marsh. Sure we all may have to eat a few midges and swat away a few green-eyed flies, but I get to stay active and learn at the same time. This is my dream job, and I am living the dream.