I am the type of person that attributes songs to the work that I do. And after my first day sampling for benthic algae last summer, I already had the chorus of the Beatles’ Twist and Shout running through my head.

That may seem an odd choice of song, but I assure you that there is no better musical masterpiece to describe the complete process of benthic algae sampling and running. In the field, with our four-centimeter diameter corers, we cut back the cordgrass Spartina patens in the high marsh to reveal the sediment beneath. The dense Spartina patens roots woven through the soil, however, force us to twist the corer to break up those roots, eventually releasing our sediment core sample. There we have the lyrics “Twist and shout,” shouting in joy (or frustration) optional.

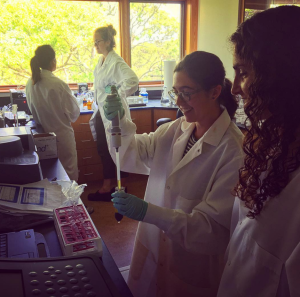

The next week, I travel with my samples back to the lab at the Woods Hole Research Center, where I extract the cores in acetone before running them on a UV Spectrophotometer, to measure chlorophyll a absorbance at different wavelengths of UV light (which, in turn, tells us benthic algae abundance). With running the samples, though, comes a lot of tube shaking, after adding acetone and again before being spun down in the centrifuge to run on the Spectrophotometer. Hence, “Shake it up, baby, now.” Shake those samples!

If you couldn’t already tell, I’m quite passionate about benthic algae, the topic of my independent research. However, it took a little while for this interest to grow on me.

The first time I heard the words benthic and algae together was last summer, when it was proposed by the Lead Principal Investigator Linda Deegan that I be in charge of field sampling, organizing the past fifteen years of data, and eventually finding the story behind the microalgae response to nitrogen fertilization. I did my best to act knowledgeable about the topic, but in my two years of undergraduate study, I had only come across macroalgae, and never algae described as benthic. Cue the background research!

What we refer to as benthic algae is microalgae, such as cyanobacteria and diatoms, found in the first few centimeters of marsh sediment. Benthic algae is important for the uptake of nitrogen and carbon, and serves as a source of energy for grazers, among a myriad other things. This algae is also resilient to many environmental factors like extended darkness and hypoxic or anoxic environments, which means that it could play a role in salt marsh recovery from nitrogen loading; but should benthic algae be negatively affected by that nitrogen addition, there could be potential consequences for the salt marsh ecosystem.

Through research, I began to see benthic algae as a link between marsh invertebrate ecology, a topic I was familiar with and loved, and biogeochemistry, an area new to me when I began with TIDE. Armed with my corers in the field, a UV Spectrophotometer in the lab, and fifteen years of historic data in the office, I hope to unlock the full, fifteen-year story of how benthic microalgae responds to nutrient loading and marsh recovery this upcoming year.

– Kate Armstrong

google.com

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice whilst you amend your website, how could

i subscribe for a blog site? The account aided me a appropriate deal.

I were tiny bit familiar of this your broadcast provided vibrant clear idea

google.com

You actually make it appear so easy together with your presentation however I in finding this matter to be actually something which I feel I would by no means understand.

It seems too complex and very extensive for me. I am looking ahead on your next put up, I’ll try to get the

hang of it!